A Few New Mexico Fungi

Fungi are not plants, but their own kingdom. Mushrooms are the reproductive bodies of fungal masses. In 2021, thanks to fortuitous rains, mushrooms sprang up in the Sandias like, well, mushrooms. What was most amazing was not their quantity but their variety. I was forced to get serious about my mushroom photos.

I am not a mushroom expert. If you rely on my species guesses when considering whether to eat a mushroom, you're angling for a Darwin Award. Eating a mushroom in the wild may not make you sick, but not eating it is guaranteed to not make you sick.

I check my photos against the New Mexico observations on Mushroom Observer, and have submitted many of them to that web site for others to identify. I have also had help from Michael Kuo, both directly and by looking at his web site.

Even so, these photos represent one person's voyage of discovery, wrong turns and all. If you see something I've misidentified, please let me know via my "Contact" page, which is tabbed at the top.

Images are organized alphabetically by taxonomic unit, up to order. Hover over a photo series to control the images. I discuss lichens, which are symbiotic colonies of fungi and algae, on a separate page. My only photos of slime mold are also on a separate page, since slime molds are not fungi (even when they look like they should be).

Agaricales (Gilled Mushrooms)

Agaricaceae: Agaricus

This mushroom in a city park looked like one I might buy in a store. Not surprising, since "button mushrooms" are Agaricus bisporus, one of the roughly 400 species in the genus. Many of those species are edible but but some are poisonous. Don't find out the hard way that your ID was only accurate to the genus level.

Agaricaceae: Desert Stalked Puffball (Battarrea phalloides)

The ground at the base of this fallen mushroom had been pawed by some animal, which perhaps was looking for a meal.

Agaricaceae: Puffball (Lycoperdon)

As Michael Kuo explains, "puffball" is a popular term that cross-cuts mushroom taxonomy. To see why certain mushrooms are called puffballs, check out this YouTube video (which may or may not be of Lycoperdon).

Amanitaceae: Fly Agaric (Amanita Muscaria)

These are sometimes called "Deadly Amanita." In August 2019 I found a number of brown amanitas but as a guess, that was due to age or a lack of moisture.

Amanitaceae: Grisette? (Amanita vaginata?)

This mushroom lacks a ring on the stem, which fits with the species description.

Mycenaceae: Xeromphalina

I found a large cluster of tiny gilled mushrooms growing out of very rotten stump (either fir or spruce). To get a better sense of the scale, look at the examples in the palm of my hand.

Nidulariaceae: Bird's Nest Fungi

The fungi of this family feature small mushrooms that are rounded at first, then open into what looks like a bird's nest with multiple eggs. In both photos, the tip of an index finger provides a sense of scale.

Pleurotaceae: Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

"The" oyster mushroom. According to Michael Kuo, "Easily recognized by the way it grows on wood in shelf-like clusters; its relatively large size; its whitish gills that run down a stubby, nearly-absent stem; and its whitish to lilac spore print. It appears between October and early April across North America, and features a brown cap."

Pleurotaceae: Aspen Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus populinus)

Pleurotaceae: Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus pulmonarius)

Not to be confused with "the" oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus.

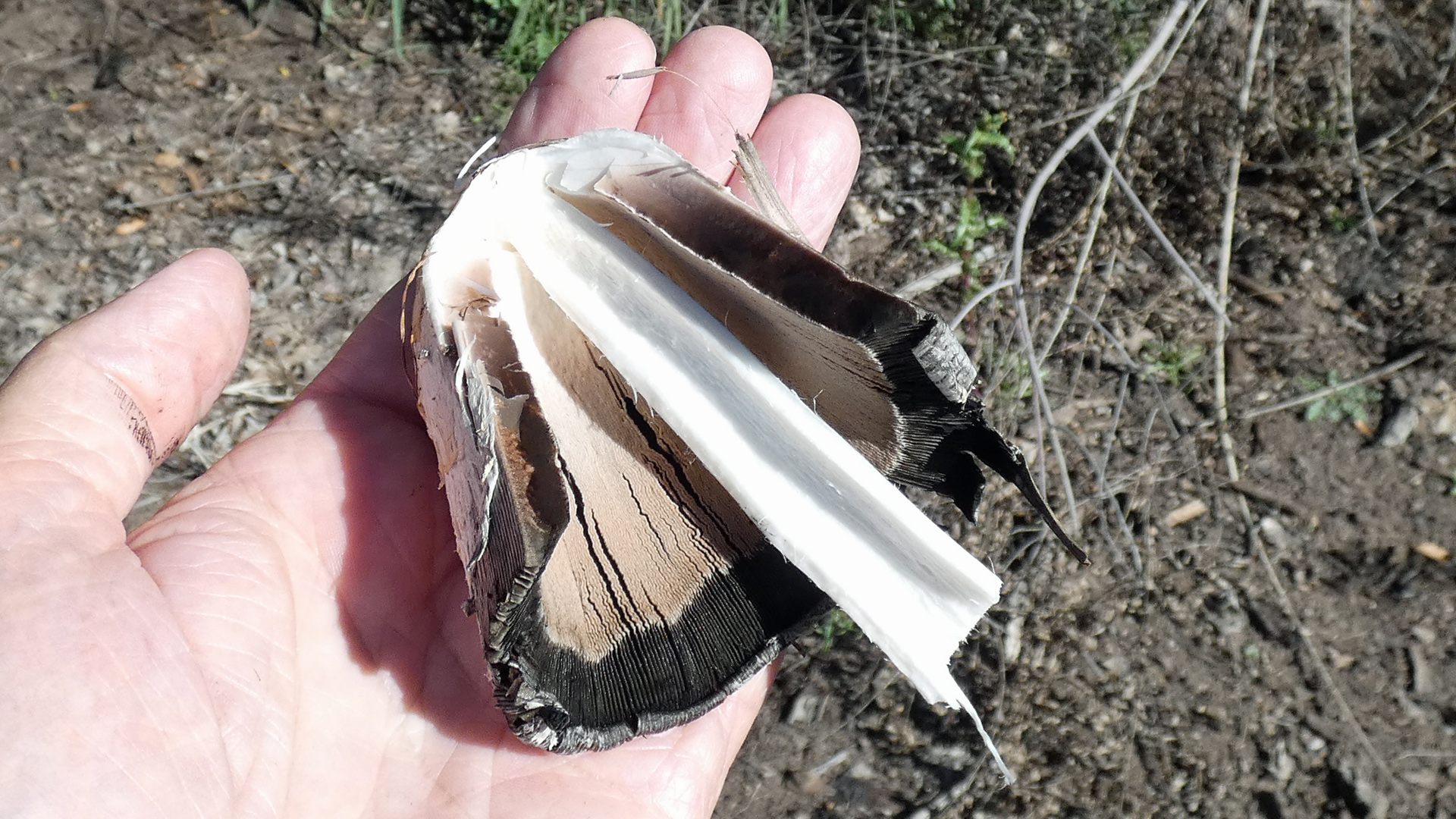

Psathyrellaceae: Inky Cap (Coprinellus?)

In recent years, the classification of the inky cap mushrooms (Psathyrellaceae) has become complicated. If you read Michael Kuo's essay on the inky caps, you'll understand why I'm noncommittal about IDs for that group.

Psathyrellaceae: Inky Cap (Coprinus?)

Psathyrellaceae: Japanese Parasol or Pleated Inky Cap (Parasola plicatilis)

This was a solitary mushroom in the middle of the lawn at a city park.

Schizophyllaceae: Split-Gill Mushroom (Schizophyllum commune)

So-called split-gill mushrooms look like miniature wood ears, but with gill-like folds in their undersides. They attach directly to trees (i.e., without stems). My photos show dried-out examples of Schizophyllum commune, which occurs around the world. This species has more than 28,000 sexes, assuming you define the word "sex" loosely. If the notion intrigues you, check out this web page.

Squamanitaceae: Floccularia

Strophariaceae: Gymnopilus

Strophariaceae: Pholiota

Auriculariales

Auriculariaceae: Jelly Fungus (Auricularia)

The Wikipedia article on jelly fungi admits that while few are poisonous, most of the rest taste like dirt.

Boletales (Boletes and their Allies)

Boletaceae: bolete mushrooms

On bolete mushrooms, the underside of the cap looks spongy rather than having gills. (They're not the only mushrooms for which this is true.) The brown examples from 2019 may have suffered from a lack of moisture.

The next set of photos shows "blue-staining" bolete mushrooms. When I turned them over to inspect the undersides of the caps, I damaged one of them. The damaged area rapidly developed a dark stain—a characteristic of multiple species within the family.

Capnodiales

Mycosphaerellaceae: Septoria Leaf Spot (Septoria)

Here you see two sides of a cottonwood leaf. I'm identifying this as Septoria, as opposed to some other leaf spot fungus, based on (1) the light spots with dark margins and (2) the host plant. Many species of fungus cause leaf spot, on a variety of plants; this is just one example.

Dacrymycetales

Dacrymycetaceae: Calocera cornea

Dacrymycetaceae: Dacrymyces chrysospermus

Gloeophyllales

Gloeophyllaceae: Gloeophyllum sepiarium

Gomphales

Gomphaceae: Turbinellus kauffmanii

Hymenochaetales

Hymenochaetaceae: Inonotus munzii

According to one publication, this fungus "is one of the main decay fungi of willow and cottonwood in the Southwest."

Phallales

Phallaceae: Common Stinkhorn (Phallus impudicus)

The dark, stinky goop exuded by this family of mushrooms has evolved to attract flies. The latter then fly off somewhere, spreading the spores. I found this example in a well-watered flower bed—a not uncommon thing. My thanks to Michael Kuo for his help with the ID.

Polyporales

Fomitopsidaceae: Fomitopsis schrenkii

This was the biggest mushroom I'd ever seen. Recent DNA studies led to this species being split off from red-belted conks.

Polyporaceae: Coriolopsis gallica

The small caps of this fungus grow wood ear style (i.e., without a stem). The host species include cottonwoods, willows, and on occasion other species. Most of my August 2022 pictures are from this fungus growing in a downed cottonwood trunk. By the time I revisited the same fallen trunk in September 2022, the caps were more extensive. One August 2022 shows this same species emerging from the base of the door on the front of my house. To ID this species, look for a cap with a very hairy brown top and pores that are angular or elongated rather than rounded.

Polyporaceae: Cryptoporus volvatus

Polyporaceae: Funalia

Polyporaceae: Trichaptum abietinum

Russulales

Auriscalpiaceae: Crown-Tipped Coral Mushroom (Artomyces pyxidatus)

Peniophoraceae: Peniophora rufa

Russulaceae (Brittle-gills and Milk-caps): Russula

Russulaceae (Brittle-gills and Milk-caps): Lactarius